What's wrong with writing about motherhood

An explanation of why there aren't more poems about breastfeeding

In my day job at WBUR, I’m often tasked with writing the “topnote” for Cognoscenti’s weekly newsletter. The topnote is a mini-essay of sorts. It’s usually inspired by or in reaction to one of the pieces we published that week. And, more often than not, what I write is motherhood-related or motherhood-adjacent. I’ve written about my daughter’s seizures, my oldest son’s difficulty with transitions as a toddler, dropping off kids at college. And this week, I wrote about a dream I had during a high-risk pregnancy. But I almost didn’t write that because I have started to worry that I write about motherhood too much.

I’ve been slightly embarrassed about this for a while. But why? If you add up all my children’s ages, I’ve got 63 years of mothering experience. If you count the years concurrently (like prison sentences), it’s only 24 years, but that’s longer than I’ve ever done any other job. Longer than I’ve ever lived in one place. How is that not significant? How could that not be worth writing about?

Of course, deep down, I know that it is worth writing about, mostly because I love reading about other people’s experiences of being a mother. Just the same way I love reading about other people’s experiences of being lots of things that I can relate to: an employee, a daughter, a runner, a writer, a wife. Seeing your experiences reflected — and elucidated — in another person’s writing feeds your soul. So why don’t we see more of that when it comes to mothers? And when we do see it, why do we minimize it? Quite simply, I think we’ve so successfully devalued and marginalized mothers (and the care work they do), that we lack the imagination to center their experiences, to see them as worthy of discussion.

For me, this all started with organized religion, which glorifies motherhood as women’s calling. But to quote the superband Boygenius, that storyline is one where women are “always an angel, never a god.” And now as a woman who makes her living reading and writing, I see this glass ceiling for mothers (and the subject of mothers) everywhere. In her book, “Screaming on the Inside,” NYT columnist Jessica Grose explained that “whenever something gets associated with women, no matter how vital it is to the world, it is seen as frivolous and nonessential.”

You see this on social media, where, as the writer Meg Conley has explained, in our “exhibitor economy” moms are financially compensated for the performance of care work — e.g., cleaning and cooking on Instagram — but not the actual care work itself. You see it in the idea that breastfeeding is free. Because in our capitalist culture — where time is money — breastfeeding is only free if mothers’ time is worth nothing.

In her fabulous collection of essays — “I’ll Show Myself Out” — Jessica Klein writes that we’ve all internalized the idea that the word “mommy” diminishes whatever noun comes after it. To illustrate, Klein invites her reader to think about their gut reaction to the phrase “mommy blog.” She writes:

Personally, I’ll confess, it always strikes me as mosquito-ish, something small and trivial. … I guarantee you if Ernest Hemingway were alive and writing an online column about his experience of being a father, no one would call it a “daddy blog.” We’d call it For Whom the Bell Fucking Tolls.

“In popular culture,” she continues, “ at least in America for the past forever years, what mothers do is seen as so unremarkable it’s not just an unimportant story but not even a story at all.”

The Danish poet and novelist Olga Ravn experienced this firsthand. New motherhood was such a mindblowing experience for Ravn that she kept asking herself, “Why aren’t there more poems about breastfeeding?” Her book, “My Work,” came out of her postpartum depression. “I wanted to have no fear, I wanted desperately to name all these frightening, weird things, I wanted to deepen my relationship with art and writing, and this material took me deeper than anything,” she says. But the resulting book was often relegated to shelves labeled “books about motherhood.” “I find it ridiculous,” she continues. “It’s nothing more than elegant misogyny.”

At 52, I’m self-aware enough to realize that I’ve internalized this particular brand of misogyny, which is embarrassing no matter how elegantly it was packaged. And I agree with Rvan when she says we need as many stories about childbirth as we need about war.

Consider this: Today, there are about 18 million veterans in the United States. (A veteran is someone who served in the military; they may or may not have seen combat and thus have firsthand experience with war stories.) There are nearly five times as many mothers — about 85 million. Perhaps even more compellingly, every American — every human — has a mother. Talk about a large potential audience.

Still, motherhood is not an easy topic. Motherhood is political. That’s never been more apparent to me than it is In this current election cycle. Everything from how we become mothers to the ways we mother on a day-to-day basis — even the choice of whether to become a mother or not — has been politicized. But this is nothing new. In 1976, the poet and essayist Adrienne Rich wrote, “Mothering and nonmothering have been such charged concepts for us, precisely because whichever we did has been turned against us.” The least we can do is not turn motherhood against ourselves.

To that end, I am learning to believe that my stories about motherhood — that anyone’s stories about motherhood — are no less important than Hemingway’s story about the Spanish Civil War, Herman Melville’s story about whale hunting, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s story about lost love and classism or J.D. Salinger’s story about 48 hours in the life of a 16-year-old boy. The skeptic will say that I’m talking about the plots of these books, not what they’re really about. Fair enough. The skeptic will say those books are about the “human condition.” Fair enough. These books are about the human condition the same way Toni Morrison’s “Beloved,” Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale,” and Amy Tan’s “The Joy Luck Club” are all about the human condition. Just because they center motherhood doesn’t make the latter titles any less worthy of our attention.

I made three humans from scratch and kept them alive. I stood with them — between the known and the unknown — and ushered them through. If that’s not worth writing about, I don’t know what is.

P.S. If you want to read the topnote about my pregnancy dream when it publishes this weekend, you can subscribe to the Cog newsletter here.

Also on my mind

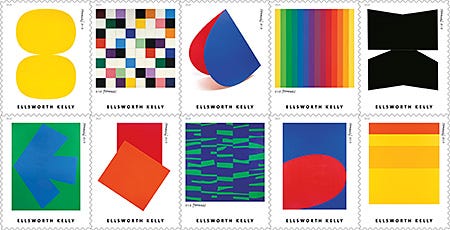

Get thee to the post office to buy these Ellsworth Kelly stamps ASAP.

Photo: USPS.com .

“A bottle of water per email: The hidden environmental costs of using AI chatbots” from the Washington Post.

It’s the signature look of one of presidential candidates. And, yes, it’s time to rename the pussy-bow blouse.

I wish “Deadloch” were more dramatic and less comedic, but that didn’t stop me from bingeing the whole series this week.

A report about international adoption from The Associated Press in collaboration with Frontline made headlines this week. At Cog, we had this brave commentary — “I willingly, joyfully adopted my sons from Paraguay. I would never do it again” — from Marjie Alonso, who adopted her two sons from Paraguay in 1995, in response.

Tara Dower shaved 13 hours (!) off the speed record for hiking the Appalachian Trail.

Winter is coming. Stock up on CeraVe SA cream (not the lotion) in a tub (not the bottle with the pump) before your skin gets any drier.

Photo: CeraVe.com “The minivan is the best car ever and that is a hill I am willing to die on.”

—Me, a three-time minivan owner

—Ian Bogost, The Atlantic

And this week’s poem:

“Forehadowing” —by Sarah Green The ash tree is sick and has to be cut down. The string lights break. The handsome mayor's begun to lose the people's confidence. A squirrel runs in cirlces and falls over. The lost dog won't let me tether it. Our neighbor strips on his porch, out of his mind. The monarch with the deformed wing does not live happily among the zinnias like I promised the children. Look—one hydrangea's blooming in two different colors. A man sleeps next to me like pillows put there to resemble a man who is right here, keeping his vow.

Thank you Kate for making me feel seen. I look forward to your beautiful writing in my inbox each week. My girls are 2 and 4 and it’s nice to feel like someone has been there, survived it, and lived to write (eloquently) about it!

“Mothering and nonmothering have been such charged concepts for us, precisely because whichever we did has been turned against us.” The least we can do is not turn motherhood against ourselves.

This particular quote summarizes the absolute disbelief and sadness I felt as a new mother, and successful businesswoman, trying desperately to find a place to have an honest conversation about the right next step for me. Every option I found was so polarized, set in their own beliefs, that I never felt I had a space to discuss the merits of each approach to mothering FOR ME. It's such a personal journey but it does take "a village" so to speak, an honest retelling of experiences. Articles like yours set that stage. Thank you for continuing to write so bravely about this topic.