Parkinson's Law, parenthood and the month of May

Parenting, like work, expands to the amount of time available for it

I was pregnant with my first child, working as a fitness and health editor at Weight Watchers Magazine, when my publisher sold the title back to H.J. Heinz, which owned the famous weight loss centers. That’s how I found myself 10 weeks pregnant and out of work. It wasn’t all bad. I had been thinking about becoming a freelance writer when I became a mom anyway. So that’s what I did.

Nine years later, I had an 8-year-old, a 5-year-old and a 2-year-old. I was primarily a mom, but also a contributing editor for another national women’s magazine that no longer exists, and wife to a guy whose job was getting bigger and bigger every day. I couldn’t figure out how to do it anymore and I quit work. (Oh, how I’d love to travel back in time to talk to my younger self. To tell her to make a different decision. But that’s a story for another essay.)

I figured I’d go back to work when things got easier. It took me about six more years to realize that it was never going to get easier. Six years. So when my kids were 14, 11, and 8, I went back to work. It didn’t happen all at once. When I was finally offered a full-time gig, it was a temporary one. In many ways, that was perfect. I signed a three-month contract with a consulting company. I thought of it as an experiment to see whether full-time employment could work for me, whether I could keep all the trains on the track at home and have a career.

Much to my surprise, I could.

Don’t get me wrong: It wasn’t easy. It was a big adjustment — for all of us. But I was pleasantly surprised that I was somehow able to compress my parenting duties while expanding my professional role. Because I had been a full-time stay-at-home mom, I couldn’t imagine keeping all of those balls in the air while also working outside the home. But eventually I realized that I had allowed motherhood to expand to the time allotted for it, which was 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

This idea that work expands to the fill the time available for its completion is known as Parkinson’s Law. The term was originally coined by a naval historian, C. Northcote Parkinson, in an essay he wrote for the Economist in 1955. (If you have a subscription to the Economist — I don’t — you can read that essay here.)

I’m the parent of a high school senior. In this whole discussion re; why Americans aren’t having more children, I’d like to present my May calendar as exhibit A.

The internet tells me that the essay includes an illustrative anecdote about a woman who has one single thing on her to-do list (it’s a good thing I can’t access the article because I would have stopped right there; I’m not a fan of science fiction). She needs to send a postcard. It is, according to Parkinson, a task that would take a busy person just a few minutes. But because this woman has so much free time (I’m still having a hard time suspending my disbelief here), it takes the woman all day. She spends an hour finding the postcard, 30 minutes looking for her glasses, 90 minutes to write her message, 20 minutes deciding whether or not she’ll need an umbrella for her walk to the mailbox, etc. You get the picture.

Most often, people use Parkinson’s Law to discuss productivity. You’ll hear lots of examples of software engineers who tend to start making progress only at the end of a two-week sprint. Or university students who don’t start a project they’ve known about all semester until the week before it’s due.

In my own life, I feel the effect of Parkinson’s Law all the time — especially with work. I’m a part-time employee. I’m supposed to work three days a week. But it’s easy to let boundaries dissolve, and to let the work expand. Lately, I’ve been trying to really hard to resist this expansion, to stay offline on the days I’m not supposed to be online, to respect the boundaries I’ve set for myself (those, after all, are always the hardest boundaries to respect).

The other arena where I see Parkinson’s Law in action is parenting. Think about how when you had your first kid you couldn’t imagine having a second. “How does anyone manage it?” you asked yourself. But then you had a second and somehow it worked. There wasn’t more of you to go around, but somehow you squeezed the parenting of two kids into the time block you had originally dedicated to one. Some of that can be explained by economies of scale, and some of it is the kind of efficiency wizardry people who write about Parkinson’s Law focus on. But a lot of it has to do with changing our expectations, doing less and being OK with that.

Because it’s May, a month that some parents refer to as “Maycember” because of the end-of-year busyness (sports banquets, awards ceremonies, recitals, class parties, finals, AP exams, prom, field trips, moving-up ceremonies and graduations — not to mention the work required to plan for summer childcare and adventures!), it’s especially easy to spot Parkinson’s Law in the wild. This month, the obligations of parenthood fill as much of the calendar as we allow them to.

I’m the parent of a high school senior. In this whole discussion re; why Americans aren’t having more children, I’d like to present my May calendar as exhibit A. It’s honestly a bit ludicrous. And it’s easy to be tempted by the cult of productivity (my favorite cult), to think that there’s some way to hack today’s intensive parenting, but I think it all goes back to boundaries.

Look, I’m not proposing you be the only parent who skips the fourth-grade recorder recital or the pre-K “graduation.” We all know that’s not the answer. But I think we can be the parent who makes a note of how exhausting the end of the academic year is and signs up for fewer committees come next September. Or the parent who raises their hand at the parents’ association meeting, when the intensive parenters are being particularly intense, to remind folks that enough is enough. To advocate for doing less. Or at least for the kids doing more without an audience present, or for the kids to do the planning and clean up themselves.

And if your kids are older, it is OK to be absent sometimes. It’s actually an opportunity to model handling tough choices, to explain that this new school tradition that has been oh-so-conveniently scheduled in the middle of your workday is one you’ll have to miss, but that you can’t wait to hear all about it. To tell them that Dad will go to events A and B and you’ll attend C. And maybe, just maybe, if all the stars align, you’ll attend X, Y and Z together.

Good luck out there.

Also on my mind

This may be the greatest eyewitness interview of all time.

This Hard Fork podcast from March about a Columbia engineering student who figured out how to use AI to cheat on job interviews was fascinating. He got suspended from Columbia, but on Sunday he announced that his startup, Cluely, has raised $5.3M to help people cheat on “everything.” This is a good one to discuss with teenagers — so many thorny issues.

I read two fabulous stories about fashion and shopping this week: “Tariffs or not, now is the time to break your bad shopping habits" from The Washington Post and “The More Clothes Manifesto” from

here on Substack. I wholeheartedly recommend both if you’re interested in becoming a more thoughtful consumer.Need Friday night plans? Watch “Dying for Sex.” OMG, this cast: Jay Duplass, Michelle Williams, Jenny Slate, Sissy Spacek and David Rasche?! Gah!

These “Sheet Pan Lemon-Ricotta Pancakes,” which my husband made for Easter brunch, were a little complicated, but so delicious and you can make most of the recipe ahead of time.

This essay about the things we lose and becoming “unattached” by

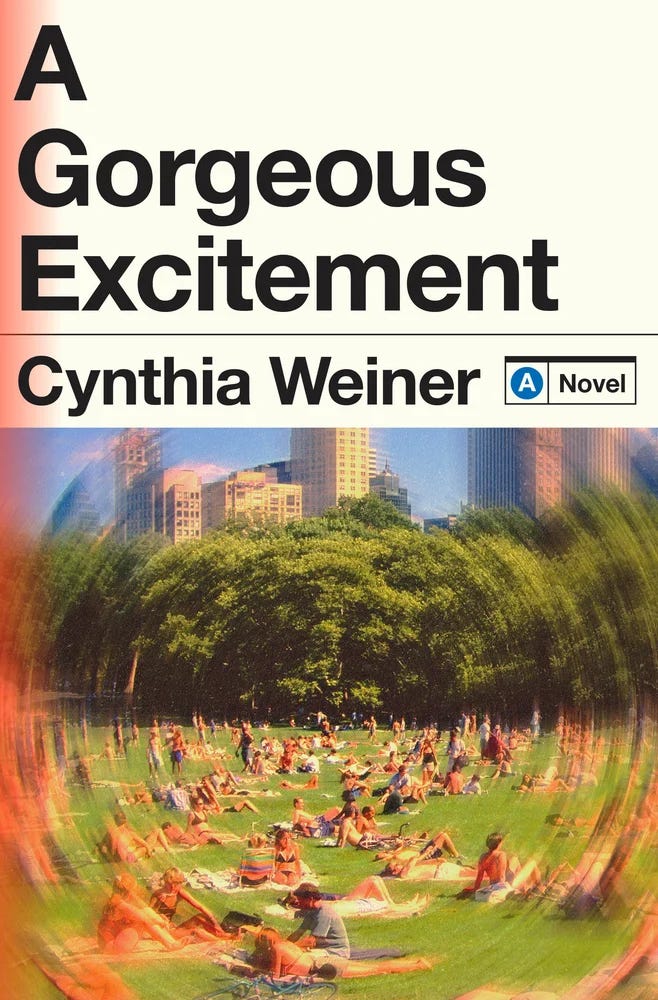

will take your breath away.“A Gorgeous Excitement,” is a tale of teenagers on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in the 1980s. I’m reading it on the Bookshop app and thrice this week, I have read until I fell asleep and dropped the phone on my face — it’s that good.

Image: Bookshop.org Happy Tiny Desk Contest season to all who celebrate.

My favorite two sentences of the week came from

, who wrote “We Have to Talk About Le Creuset”:You guys get to have your Catholic Guilt and make it everyone’s problem but when I display a little Episcopalian Fear of The Uncouth suddenly we’re intolerant. I see.

And, to close National Poetry Month, a poem from one of my favorite novelists:

The Gray Room — by Wallace Stevens Although you ist in a room that is gray, Except for the silver Of the straw-paper, And pick At your pale white gown; Or lift one of the green beads Of your necklace, To let it fall; Or gaze at your green fan Printed with the red brnaches of a red willow; Or, with one finger, Move the leaf in the bowl — The lef that has fallen from the branches of the forsythia Beside you. What is all this? I know how furiously your heart is beating.