We spent Thanksgiving 2002 with my parents. My son Ned was two and had recently started sleeping in a twin bed. I was pregnant and napping on the couch when my mom came to tell me Ned was awake. “Already?” I asked, disappointed that the end of Ned’s nap meant the end of mine, too. I trudged up the stairs, hoping to coax him back into bed, and noticed the doorknob spinning back and forth. The door was locked from the inside, and Ned was stuck, all alone.

Because the door was original to my parents’ historic home, we were reluctant to do anything that might damage it. My brother Tom examined the lock on another bedroom door and tried to talk Ned through unlocking the door himself. Initially flattered by comparisons to Bob the Builder, Ned soon gave up. He plopped down on his soggy diaper, waiting to be saved.

Luckily, in addition to an incredibly complex locks, this home has gaps between the bottom of the doors and the thresholds. At my sister-in-law suggestion, I slid a few cookies into the dark void and assured Ned that help was on the way. He was quiet and calm for a few minutes, but his patience ran out with his last bite of cookie.

“Get in here and get me out, Mommy,” he cried. “Come here,” I said, waving my hand under the door. “Hold my hand.” And we both lay on our tummies, holding hands under that old door, for 20 minutes. In the meantime, my father “borrowed” an extension ladder from a nearby construction site, climbed up it, and pried open a bedroom window from the outside, becoming a hero in Ned’s eyes and mine.

That Thanksgiving I got a glimpse of what it would be like to raise teenagers, to be frantically waving my hand under a door, trying to comfort a child who feels scared and hopeless, but not actually being able to do anything to help. And while toddlerhood and the teenage years are very similar in some ways — the temper tantrums, for instance — there are fundamental differences. A toddler needs you to open the door to rescue them. A teenager usually needs you to keep it closed. Most of the time, the teenager is going to refuse your hand, too.

And that’s OK. In fact, it’s necessary. If there’s one thing I’ve learned from parenting three teens it’s this: I can’t learn life’s lessons for them. Moody, disrespectful, irresponsible teenagers don’t become the adults we want them to be if we always come to their rescue — if we keep the doors between us cracked open.

And yet, we keep trying. We download Life 360 on our kids’ phones, believing that by knowing where they are we can somehow keep them safe. (Newsflash: We can’t.) We join the kid’s college parent Facebook group thinking an informed parent is a better parent. We monitor their every grade in the digital classroom portal. But at what cost to them? And at what cost to us?

Wendy Mogel, my favorite parenting expert and author of The Blessing of the B- , describes the struggle this way:

Well-intentioned parents perceive the world as so competitive and dangerous — there are only 10 good colleges, the drugs are stronger, sex more dangerous — that they wish for their child to go straight from sweet third grader to junior statesman. They hope that with the right strategy their child can skip the stage of adolescence — of risk-taking, bad choices, oversleeping and sketchy friends — entirely.

But the truth is, despite the horrific fact that guns are now the number-one cause of death among children and teens, our children are growing up in a much safer time than we did. It’s true. There is less crime now than there was when today’s parents were growing up. Still, we’ve somehow convinced ourselves that we can’t take any chances. This disconnect creates problems.

Last year Peter Grey, a professor of psychology at Boston College and co-founder of Let Grow (a nonprofit dedicated to childhood independence) wrote about the continuous rise in depression, anxiety, and suicide among children and teens over the last 50 years. “This increase in suffering has occurred during a period in which young people have been subjected to ever-increasing amounts of time being supervised, directed, and protected by adults,” he writes. “In school, in adult-run activities outside of school, and at home—and [they] have experienced ever less opportunity to play freely and in other ways pursue their own interests and solve their own problems.”

What does that look like in practice? Eleven or 12 years after the Thanksgiving incident, Ned was riding his bike to a friend’s house. He called me from his flip phone to tell me he was lost. “Hang up and send me a photo of where you are,” I said. So he did. And then I called him back. “You’re in a safe neighborhood and you’re not too far from Jack’s,” I explained. “Give it another 15 minutes and if you’re still lost, call me back.” But I didn’t hear from Ned again. After figuring it out on his own, he arrived at Jack’s and was having so much fun that he forgot to tell me he had arrived. “All good?” I finally texted after waiting 30 minutes. “Sorry, Mom,” he texted (but without capitalization or punctuation.) “All good.”

Now, to be fair, that’s an anecdote from the early teen years (which are downright adorable in comparison to the terror of the late teens). So how do you keep the door closed throughout high school and college? Mogel offers profound guidance. For me, these were the biggest takeaways (in the author’s own words):

Teenagers need to make dumb mistakes to get smart.

Be alert, but not alarmed.

Be compassionate and concerned, but not enmeshed.

Love them, but do not worship them like idols or despise them when they let you down.

Be observant without spying or prying.

Pretend you have seven kids: Dopey, Bashful, Sleepy, Grumpy, Doc (the “know it all”), Sneezy (Does he have a learning disability? An undiagnosed [disability] of some kind?), Happy (Is he too laid back? Where is his passion, focus, ambition and drive?), and that whichever of these seven appear in your child’s form on any given day, they are all just going through a phase.

When they come to you in distress, resist responding like a concierge, talent agent or the secret police. Assume that they are capable of figuring out — through trial and error — how to solve their own problems.

I know, I know. It’s easier said than done. My older children are 20 and (almost) 23, so I only have one teenager left in my house. I’ve seen this film before. I know how it ends. (Spoiler alert: they’ll be fine). But there are still times when I want to fast forward through the scary parts.

Unfortunately, that’s not how growing up works. There are no shortcuts. I’ve written abut this before: the only way through it is through it. And our job as parents, I have come to realize, is to make ourselves obsolete. If we succeed, we will raise children who no longer need us. But, as they enter adulthood, I hope they’ll decide to open the door themselves, and walk out to be with us.

Hang in there,

Also on my mind

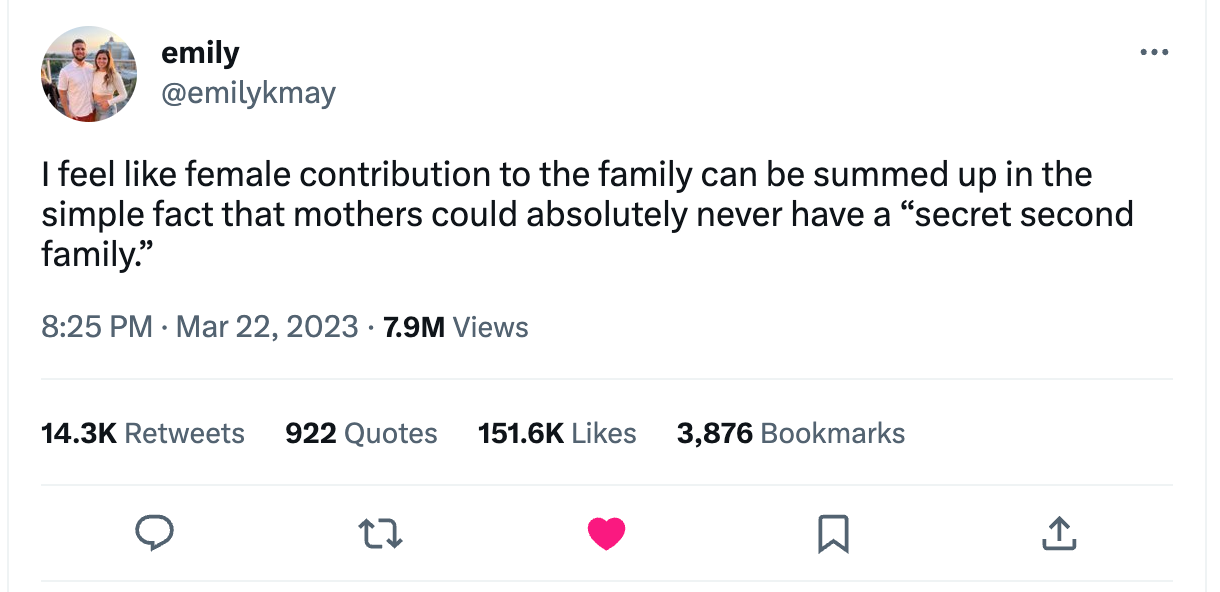

Yup.

Speaking of teenagers, it can be hard to think of things to do with them once they reach a certain age. I recently bought this LEGO orchid, thinking my 16-year-old and I could build it together. He lost interest pretty quickly, but I worked on it near him, while he watched the women’s basketball championship. The whole situation reminded me of the parallel play of toddlerhood. Sometimes, it’s just nice to be near each other, even if we’re doing different things.

When Logan Roy climbed onto a makeshift stage of boxes of paper to address the troops in the Sunday’s episode of Succession, the comparisons to Rupert Murdoch were unavoidable. This Town & Country piece takes a closer look at the similarities and differences between the Roys and the real-life families that may have inspired the show’s writers. (And while we’re on the topic of succession, I also loved this HBR article about what the show can teach us about negotiations.)

Friendship is a hot topic. Inspired by the publication of Friendaholic and Platonic and other recent titles that focus on the subject, Emma Gannon made this fun list of 19 types of friends (including the hobby friend, cheerleader friend and industry friends — not to be confused with industry “friends.”) Do you think she missed any? I don’t see the “our-kids-are-friends friend,” which describes a lot of relationships in my life.

Some have accused Elizabeth Holmes of getting pregnant to look more sympathetic. The mother of two will be sentenced later this month. But she’s far from the first mom to be separated from her children by time in prison. This eye-opening article from The 19th discusses how some states try to mitigate the devastating consequences of having an incarcerated parent.

These açai bowls with fruit and granola from Dole are my new favorite afternoon snack. If I’m feeling ambitious I add some chia seeds (read: fiber) and more unsweetened coconut flakes.

Did anyone else miss the soft launch of the newest app from the makers of TikTok? Lemon8 will initially focus on topics like fashion, healthy food and wellness. Megan Alida Strachan wrote about it in her newsletter, where she also shared some really interesting thoughts on the future of great marketing.

I can’t stop thinking about this episode of This American Life. All three stories were fabulous. But the second story, “Synchronized Swimmers,” which starts at 25:00, really had an impact on me. I’m not sure I’ll ever think about swimming in the ocean the same way again.

The Morning After Shower Cap helps me extend the life of the previous day’s blowout when I skip a wash.

I find the kerfuffle over “We Heart NYC” campaign endlessly amusing. So much to unpack.

i love you, and your way with words. rowan locked himself in our beach bedroom this summer (the bottom was NOT wide enough to pass cookies through) and we had to get our next door neighbors to take the door off the hinges. perhaps this is a metaphor for - it takes a village? i can only imagine his teenage years...

even though he's not a teen yet, your words of wisdom seem relevant and always calming to me. i especially love the 7 dwarfs - for SURE applicable to my 4-going-on-14 year old!